Books on Film: Phyllis Nagy on Carol

Phyllis Nagy discusses her adaptation of Patricia Highsmith's The Price of Salt.

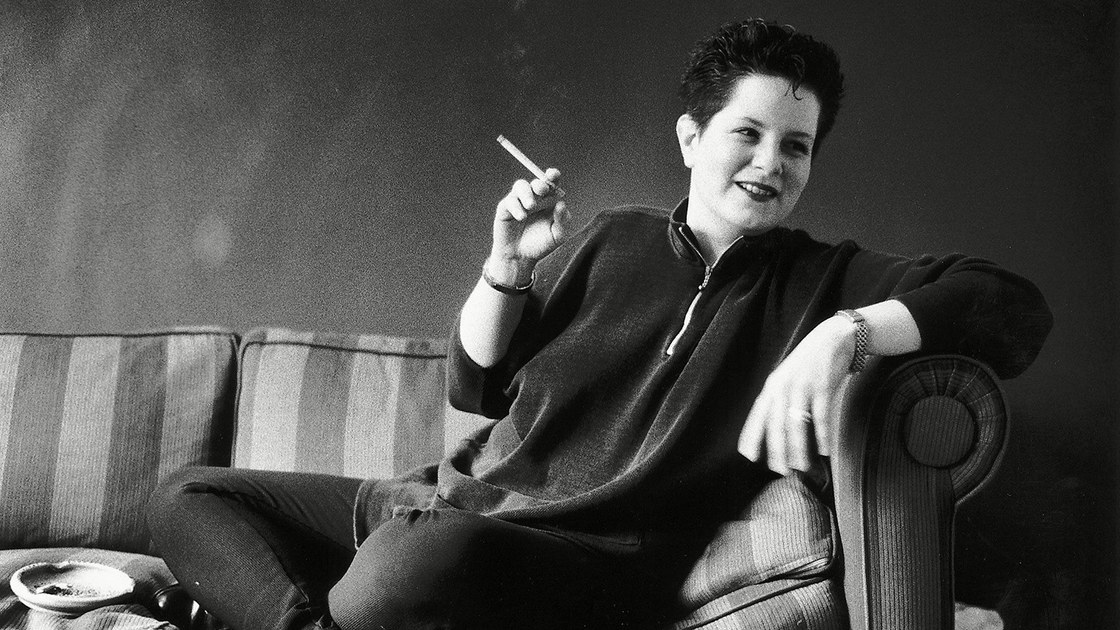

Phyllis Nagy is most well known for her lauded work in British theatre. She made her film debut writing and directing the HBO film Mrs. Harris, which starred Annette Bening and Ben Kingsley. She is most well known to North American audiences for her brilliant screenplay adaptation of Patricia Highsmith’s The Price of Salt, which became Carol. Directed by Todd Haynes, the Academy Award nominated film stars Rooney Mara as Therese Belivet a young photographer who falls in love with the older – and married – Carol Aird, played by Cate Blanchett. On May 8th, Nagy will present the film (on 35mm!) as part of TIFF’s ongoing Books on Film series. We spoke with Nagy in anticipation of the event to discuss her adaptation of Highsmith’s masterful novel.

Scene Creek: Highsmith’s novel explores desire rather differently than Carol does. Since The Price of Salt is told from Therese’s perspective, we read about how she desires Carol, but rarely about how Carol desires her. This is very different from the film in which Carol seems much more dominant. How did you craft that desire for Carol?

Phyllis Nagy: I suppose the problem with making a film from that book is just that thing. It is an internal, obviously unreliable – anyone who is in love is unreliable – point of view. Every action that we do see described in the novel that is Carol’s is filtered almost exclusively through Therese. It works brilliantly in the novel because Carol is the object of desire and that’s that. We can all project whomever we see in our own lives onto Carol. That is the great strength of that obsessive, Highsmithian storytelling there. Obviously, that’s never going to work for a film, unless it was determined that we were making a very different kind of narrative that was more experimental and less mainstream, I suppose. With [the film], the character Carol had to be invented, given just as much weight as Therese. One of the ways in which to do that is to differentiate the behavioral aspects of their respective desires.

SC: Can you talk about your relationship with Patricia Highsmith?

PN: Patricia Highsmith was a really good friend to me for the last ten years of her life. Though I spent a lot of time with her in that decade before she died, both of these things came after her death. As my career took off in London – I wasn’t yet doing films – we did talk some about how it would be nice if I worked on one of her books. Actually, The Price of Salt was not one that she enthusiastically mentioned as something that might be worthy of a film adaptation. She was more interested in other female protagonist based books like Edith’s Diary or Deep Water. So oddly, The Price of Salt was not one that she herself thought might make a good film or a film that anyone was interested in seeing. There was always that with her, that she was guarding it in some very obscure ways, even though she did finally republish it under her own name and retitled it “Carol” in the very early 90s.

SC: When looking for Highsmith’s work in a bookstore one would often have to go to the Mystery section, which would feature all her work except for The Price of Salt, which would be organized with general fiction. Do you think it is that different from her other novels?

PN: I think the novel has the same sense of hauntedness, obsession, and paranoia. As Todd Haynes often said, love is the crime. In that way, it really does fit in. It’s not like she became a different writer for it, but I think obviously it’s a very peculiar love story and one in which she completely ignored the rules of homosexual pulp fiction of the time, of which she had read quite a bit.

SC: One of my favourite symbols in both the novel and the film is the gun. In the film it is used in this excellent confrontation scene with the private detective. Can you talk a bit about that? I think it’s that pulpy moment that really connects it to many of Highsmith’s mysteries. Can you talk a bit about that?

PN: It’s funny because that gun, in all the years of development, was something that I actually had to fight very hard to keep. In film development terms, which is different than pure “we’re making movie terms”, it is because it was the outlier. Like, “Where does that gun come from? Why does she have it?” It doesn’t make sense in a neat dramaturgical, immediately apparent way, but it makes total emotional sense. As it does in the book – well of course in the book, according to Therese, Carol is a much spikier character. She is moody in the film, but she’s not as awfully dismissive of Therese in many ways, as she is in the book. That’s pure Highsmith. The gun though – the reason is worked is because it’s not explained, both in book and movie. It takes it away from the more pulpy aspects of the woman on the road with a gun at particular moment in time. It’s necessary. It’s emotionally necessary. I mean, is Carol really in any danger? Physical danger? No, I don’t expect she is. But the strength of the action, that she manages to do that, is the important thing in both film and novel. Highsmith has to get, in every one of her books, a weapon. The child is a weapon as well, much more so in the film. She only gets alluded to in the book. But she needed that, we spoke about that. There is a need for her to place people in situations in which they either are in peril, or they think they’re in peril. Much more often the latter.

SC: One of the most notable changes from the novel is that in The Price of Salt Therese works as a set designer, whereas in Carol you have made her a photographer. Where in the writing process did that happen?

PN: That happened very early, for several reasons. As I thought about and really envisioned scenes of a girl sitting in a theatre in the dark sketching – it’s not a very useful tool. If we’re going to chart Therese’s emotional growth as well, it’s not a very useful tool. It’s obscure to most people, it’s rarified. I’ve never seen a film, any film, which gets the theatre in any reasonable way. Whether it’s the particulars of rehearsal or – and the novel doesn’t get it right either to be fair. Why would it? Highsmith was not a person of the theatre and so few filmmakers are. I knew that would never work – it’s a static thing. With pictures, and her eventual evolution from being someone who is rather remote and detached and not interested in people, to someone who is very interested in a particular person, that just seemed easy and dynamic. You didn’t have to do a lot of work to get there. It just always felt right, and it accomplishes the same basic purpose.

For more information on the screening, and to purchase tickets, visit http://www.tiff.net/events/books-on-film-phyllis-nagy-on-carol/